The State of Connected Kitchens

The foodservice equipment-and-supplies industry continues to make strides toward a connected kitchen—all to benefit operators.

Wireless technology, smart equipment, the Internet of Things—these are just a few key elements that work in concert to make operations more efficient and effective in today’s modern restaurant kitchen, aka “the connected kitchen.”

“Connected kitchens have the ability to provide deep and rich insights that can steer the daily actions of our restaurants’ managers,” says Chris Johnson, chief operations officer of KFC Northern Europe. “The challenge is, of course, being able to access and unlock the data.”

What is the state of connectivity in kitchens right now? And how do we get to a place where connectivity extends beyond a talking point at conferences to something that is ubiquitous in restaurants? We talked to industry consultants, operators and manufacturers leading the charge to find out about recent advancements and what innovations they foresee in the future.

An Ongoing Evolution

Connectivity in the kitchen has been a topic of conversation in the industry for more than two decades, says Charlie Souhrada, vice president, regulatory and technical affairs with the North American Association of Food Equipment Manufacturers. In 1999, multiunit chain operators asked NAFEM to develop a standard

“We are trying to get a standard set up in the industry if you have an oven from [Brand A] or fryer from [Brand B], they all speak the same language.” —Peter Cryan, Inspire Brands

by which commercial kitchen equipment could communicate with computing devices. The organization released the NAFEM Data Protocol in 2003 and updated versions as recently as 2013. “In simple terms, it is the Internet of Things for commercial kitchens,” Souhrada says. “It is still an active standard or rules of the road for how data should be organized so that an appliance can read it.”

Since then, “there has been incremental creep in the industry’s acceptance,” Souhrada says. Why hasn’t it been more widely employed by now? One reason is that the NAFEM Data Protocol provides the road map, but the onus is on operators to employ it. “The operators need to define what they want to accomplish with this kind of technology. For example, I want to track my inventory. I want to track temperatures. I want to track the equipment energy consumption,” Souhrada says. “All of those elements are pieces of information that can be captured by using the NAFEM Data Protocol. The operator has to work with the manufacturer or the equipment engineers to establish what pieces of data they want to grab hold of and interpret.”

Also, connectivity isn’t a priority in every kitchen. “So, for example, if the operator wants to know what kind of an energy performance they are getting from their piece of equipment, they could use the NAFEM Data Protocol to do that,” Souhrada says. “But if that operator is not responsible for the utility bills, odds are they probably wouldn’t care.”

Clusters of Connectivity

For operations in which connectivity is a priority, manufacturers continue to show interest in the technology, which will likely shape what advances continue to come to market. Case in point: In 2019, two manufacturers acquired technology companies working on connected kitchen solutions, bringing this type of intel in-house.

The result, in some cases, is pieces of equipment that can talk to each other—if they’re the same brand, or brands under the same corporate umbrella. But there still is work to be done. “We are trying to get a standard set up in the industry, if you have an oven from [Brand A] or fryer from [Brand B], they all speak the same language,” said Peter Cryan, senior director of equipment innovation for Inspire Brands, in a presentation at the RestaurantSpaces show in March in Los Angeles. “Think of our home: You have a Wi-Fi box in your house and you have your phone, your TV, your computer—all your different devices—connect to the Wi-Fi box and you get internet. Basically, what the equipment manufacturers are asking us to do is not do it that way: Only talk to their gateway. Can you imagine having 20 different Wi-Fi boxes in your house to talk to all your different devices? It’s not practical; it’s short-term thinking. So, we’re gonna challenge the manufacturers. A lot of them are starting to open up to it.”

Joseph Schumaker, FCSI, founder/CEO of consulting firm FoodSpace, says that some equipment manufacturers have been reluctant to pursue connectivity with other brands or third-party software. “Most equipment manufacturers don’t want their equipment to talk to other people’s equipment. They don’t want to have open application programming interfaces (API) that allow for third parties to get in there and pull data.

KFC Northern Europe plans to connect equipment so it can view on a screen the volume of cooked food and how long it’s been holding. Courtesy of Kitchen Brains.

They play that very close to the vest … and they look at it as intellectual property,” Schumaker says. The result is a kitchen with “clusters of connectivity,” he says. “In some ways it’s a disconnected kitchen, still, by my definition.”

At least one manufacturer with multiple brands doesn’t see avoiding pursuing connectivity with other companies as a sustainable strategy, however. In 2018, it released digital services that connect its own equipment as well as equipment from other companies to help operators with management of reports, assets, menus, quality and service.

“The industry is moving toward coopetition agreements, whereby manufacturers can agree to send their data to another manufacturer’s cloud with assurances that their IP data is safe and will not be infringed upon,” says the manufacturer. The operators in these instances act as the broker between the two parties and the agreements are required for the manufacturers to sell their equipment to them. “Of course, without legal assurances, the risk is the loss of differentiating technology,” the manufacturer adds.

Sensing the Need

Seeing the need for more connectivity across brands and to retrofit legacy appliances, a few tech companies have created software platforms and networks of IoT devices—think timers, sensors and controllers—that can be installed onto any brand of equipment to deliver valuable information to operators.

Johnson says this type of tech is in the nascent stages at KFC Northern Europe. “We’re exploring sensors on kitchen hand-wash taps to monitor and flag team hand-washing compliance, temperature sensors that will allow remote tracking of all chilled and frozen storage and looking at how we can integrate remote oil-quality monitoring into our system.”

One of Johnson’s current initiatives is rolling out a cook-and-hold-time platform across KFC Northern Europe. All pressure fryers and open fryers will be connected wirelessly so that the team can view on an interactive screen important information, such as the volume of cooked food and how long it’s been holding, and a forecasted volume of food the team should prepare to meet anticipated future orders.

This system solves a number of daily challenges for staff. “[It] acts as a governance platform ensuring teams can clearly see when products are in hold time and trigger when to discard products that no longer meet our quality standards—not possible in the analog world of pen and paper,” Johnson says. “The second-biggest unlock for us is that the forecast functionality starts the cycle of being prepared for peak times, encourages our restaurant managers to plan ahead and removes the guesswork on what to prepare to meet anticipated demand. Gone are the days of the cook sticking his or her head out into the lobby to ‘get a feel’ for how busy it is.”

The Future of Connectivity

Though kitchen connectivity is gaining momentum with larger chains, it’s a long way from becoming universal.“Unless you’re a big company … not only do you not have people thinking about that, you don’t have the time, talent or the money to actually put together a system like that,” Schumaker says.

For smaller operators to jump on board, Schumaker thinks that, first, connectivity needs to be built into equipment from the get-go.

When Arby’s partnered with a third-party tech company to optimize kitchen operations with connected kitchen software and a network of sensors and devices, the company targeted energy and water savings first, and used that savings to pay for the expansion to connect other equipment. Courtesy of Arby’s.

“[Operators think,] why do I have to buy another third-party piece to plug in there? Why can’t I get that data directly from the source? That’s the fundamental problem,” Schumacher says. Second, the software platform that connects it all must have a clear value proposition. “If I’ve gotta pay for software with a monthly subscription on it that’s $200 bucks a month, but I am saving $400 a month in energy, I’m going to pay for that software all day,” he says.

Schumaker’s dream for operators is a truly connected restaurant—not just kitchen—that could surface important data from equipment, reservations systems and Big Data (data available to the public, such as weather, that impacts daily business) to give a 360° view of daily action items.

“Something as simple as reminding a manager to put out extra floor mats because there is a rainstorm coming in,” Schumaker says. “These managers have a million things going on. ‘Oh shoot, the stove’s broken. I’ve gotta order lobsters.’ What if there was an app that just tells me what matters?”

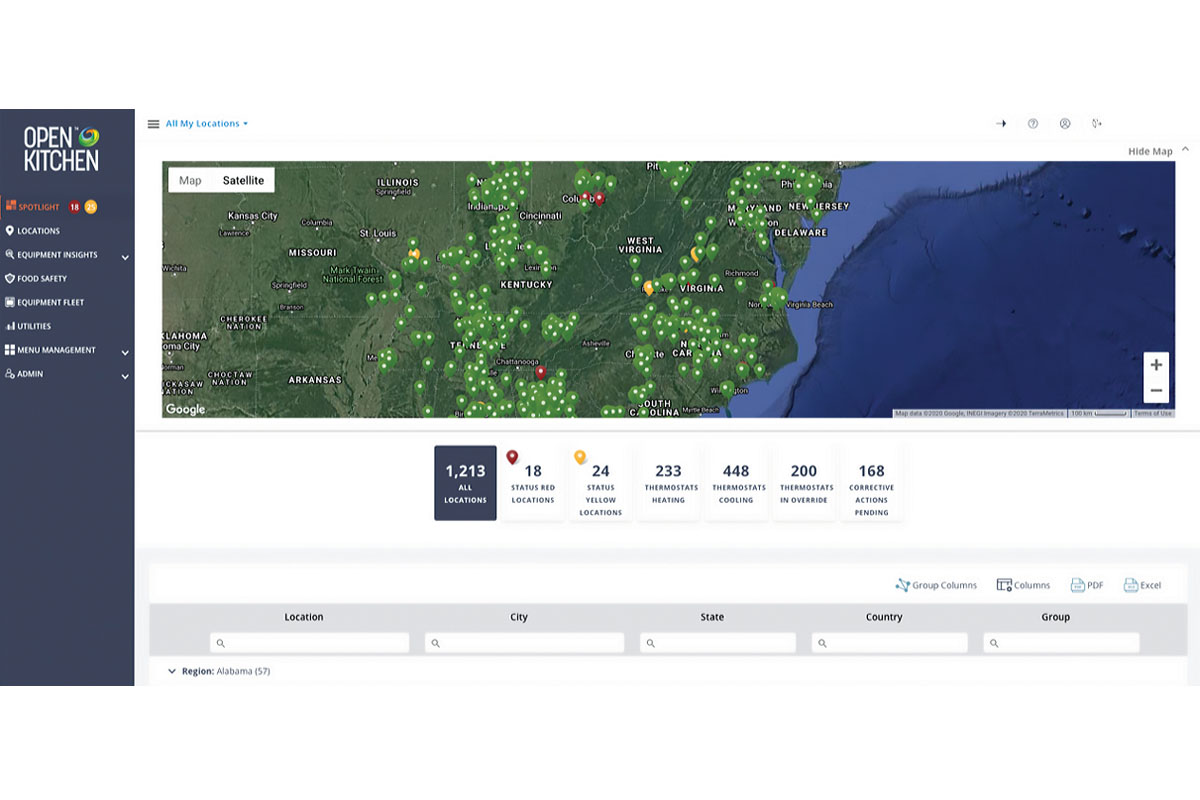

This screenshot illustrates locations with equipment needing attention. Courtesy of Powerhouse Dynamics.

RELATED CONTENT

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -

TRENDING NOW

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -