Building a Better Waste Management System

Operators typically can’t serve food without creating some amount of food waste. Managing it increasingly is a chore thanks to always-evolving city and state regulations. “Some states and cities have mandated stricter restrictions on food waste to landfill, driven by concerns about both carbon emissions and landfill space,” says Tarah Schroeder, FCSI, director of sustainability at Ricca Design Studios in Denver. “States like Massachusetts, California, Rhode Island and Vermont are limiting the disposal of commercial organic waste and requiring diversion to composting, conversion, recycling or reuse, along with cities from New York to Austin to Portland and Seattle.”

Setting up or adapting a proper waste management system requires an understanding of these regulations, which can be challenging—especially for multiunit operators—when rule variations from place to place are extreme, Schroeder says. Working with a consultant familiar with the rules is one place to start.

Joe Sorgent, FCSI, director of sustainability at Cini-Little in California, says consultants “are becoming very popular because of our role in waste management reports needed for building permits. There are city health department codes that cover buildouts of foodservice areas, city trash handling codes and state regulations in addition to what the city codes require.”

Waste management systems run the gambit. For restaurants that have simpler needs, an affordable food waste disposal solution that complies with local regulations might simply mean a scrapper, a plan for separating compostables, a contract with a hauler, and the appropriate space and receptacles to store waste until it’s removed.

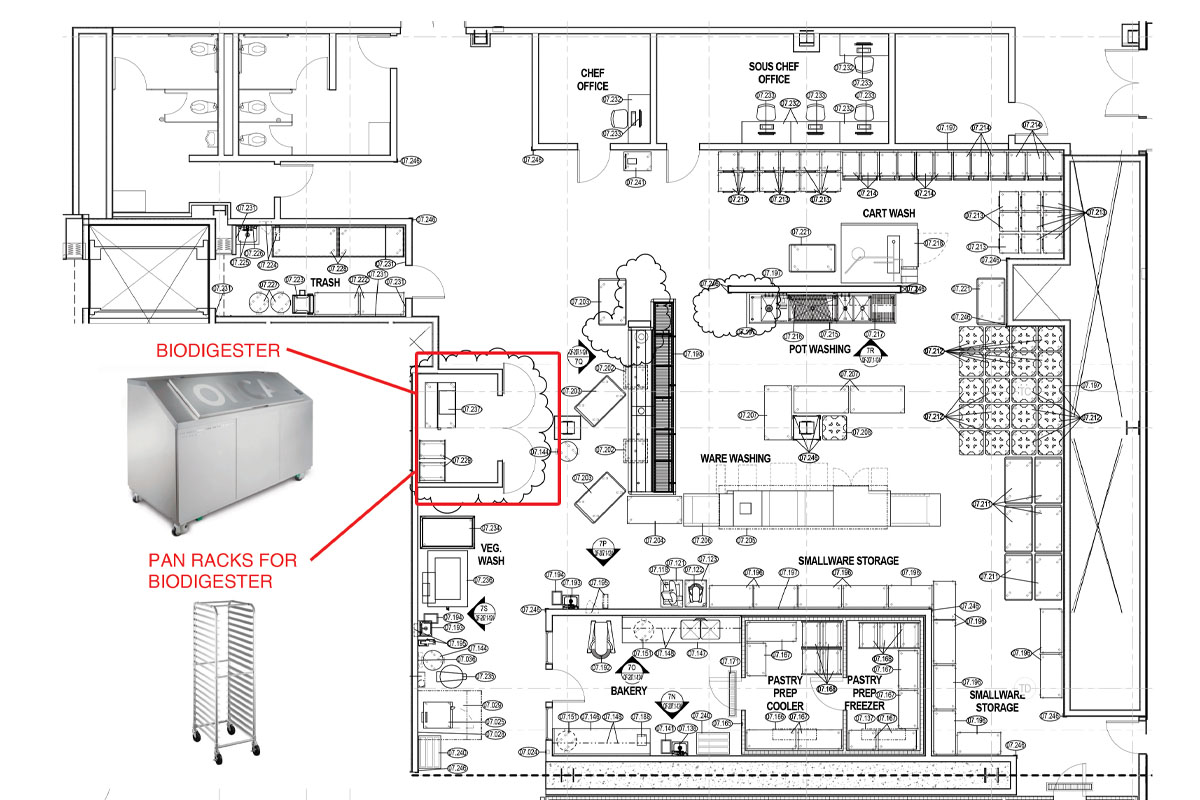

For larger institutions like hospitals, universities and hotels, consultants often work with the architects to design a more complex system. “Our services are typically for the entire facility,” says Sorgent. “We develop waste management centers and soiled and clean docks with architects. We do a waste generation estimate, break it out to recycling streams, and test and analyze different methods and equipment. Systems and equipment like pulpers, dehydrators and biodigesters are solutions to specific challenges; they have high costs, take up space and sometimes require a lot of engineering.”

If your budget doesn’t stretch to cover the waste management system you have in mind, begin with rented or leased equipment, advises Foster Frable, FCSI, president of Clevenger Frable LaVallee in New York: “Start with a smaller model, and then if business volume increases, trade up to a larger unit.” Most manufacturers offer five or six sizes of equipment for products like digesters and dehydrators to fill different operational needs, he says.

“Some states and cities have mandated stricter restrictions on food waste to landfill, driven by concerns about both carbon emissions and landfill space.” —Tarah Schroeder, Ricca Design Studios

Does your restaurant use a lot of produce, or do you rely on speed-scratch ingredients (adding a few fresh items to ready-made products)? What’s your best balance of labor costs, real estate costs, maintenance costs and utility costs to get the highest ROI over time? These factors will help determine what elements are right for your operation’s waste management needs. Here are some key components:

DISPOSERS. Reducing food waste going out the back door, under-sink disposers are handy to have even if you contract with a hauling service to remove most of your operation’s waste, because they help block bits of food from accidentally being washed down the drain. Water departments may discourage or even forbid their use, however, since they increase the load on the sewer system. Check with the manufacturers; they have current lists based on their experience.

SCRAPPERS/COLLECTORS. These units, installed in the scrapping area of a warewashing room, pair heavy-duty grinding mechanisms with recirculating water. Because they liquefy soluble food waste and wash it into the pipes while fibrous parts get trashed, they’re allowed in locations where local code bans disposers. There’s also less need for manual scraping of dirty plates and pots, and water usage is lower than with disposers. And while collectors are more expensive compared to disposers, they cost less than pulping and biodigesting systems. (The typical investment is under $10,000.)

“Start with a smaller model, and then if business volume increases, trade up to a larger unit.” —Foster Frable, Clevenger Frable LaVallee

PULPER/EXTRACTOR SYSTEMS. Like scrappers, pulpers recirculate water and grind food waste. Unlike scrappers, they can handle paper towels, cardboard, plastics and even lighter metal cans as well, says Ray Soucie, FCSI, senior project manager at Webb Foodservice Design in Portland, Ore. Instead of washing down the drain, the slurry goes to a chamber where an extractor spins or squeezes out water, leaving a semi-dry pulp lower in weight and volume than the garbage that went into the system; that pulp can go straight to the hauling dock or on to a dehydrator that will further diminish it. In addition to self-contained pulper/extractor units installed in the scrapping area, there are more complex systems that grind food waste there, then send slurry to flow through a trough to a press at the back dock to be squeezed into pulp. (Depending on the operation’s volume, ambient temperature and frequency of waste pickup, you also may require a temperature-controlled or refrigerated area near the dock to store the pulp.)

“Pulpers and extractors can be an effective solution, but they require a lot of coordination, real estate and infrastructure to install properly,” says Joshua Labrecque, Assoc. FCSI, assistant project manager at Colburn Guyette in Massachusetts. Local plumbing requirements also can be a factor, he says; some jurisdictions require grease interceptors along the slurry line, which require consistent maintenance to keep clear and clog-free.

DEHYDRATORS. These may be a standalone solution, but more often they’re a further step for ground or pulped food scraps. A heater, blower and agitator gradually dry the waste; the extracted water goes down the drain. The product that remains is only 20% the weight of the original. “A pulper or grinder combined with a dehydrator is a great system if your hauler bases his fee on weight,” says Sorgent. (It only works, however, if you keep the material dry; if it comes into contact with water, you’re back where you started.) Keep in mind a dehydrator may use a lot of energy so, factor that into calculations.

BIODIGESTERS. A biodigester or liquefier is a closed box equipped with a grinder or shredder that mechanically breaks up food waste. After that step, microorganisms or enzymes decompose the waste over an eight-to-12-hour cycle (or as little as four hours for a light load). The machine continuously adds fresh water, and there may be an agitator in the box to keep it moving around. Once digested, the slurry goes down the drain. Because biodigestion is a continuous process, employees can dump food waste in the box throughout the day. One nice-to-have feature: a built-in scale to help prevent staffers from overloading the unit at any one time.

Biodigesters are a high-end, high-volume solution, and determining whether they are the most cost-effective for a particular institution’s needs requires analyzing many factors. For instance, because periodic monitoring and regular maintenance are required, local service and support are important factors in deciding whether a biodigester should be specified for a project, Frable says. Remote biodigesters can require a lot of engineering and utility use, and getting local approvals can be a long process, Sorgent adds. But the system is highly effective at reducing food waste just the same way nature does.

A Look at Laws

In the U.S., the National Conference of State Legislatures reports, around 30 bills addressing food waste were introduced in 12 states last year. Of note:

• California, for example, now requires limited-service restaurants to place bins for recycling and food scraps/soiled paper in the front-of-house for guests to access.

• New Jersey and New York became the latest—joining California, Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut and Rhode Island—to require large commercial and institutional operators to recycle food waste.

• A number of municipalities including New York City; San Francisco; Seattle; Austin, Texas; Boulder, Colo., and others have enacted their own waste bans in recent years affecting foodservice providers.

It’s a complicated patchwork of regulations on top of waste-reduction goals set by the Environmental Protection Agency and corporations. Most are phased in, with different requirements based on how many tons of waste a business produces and its proximity to an appropriate waste-handling facility.

RELATED CONTENT

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -

TRENDING NOW

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -

- Advertisement -